Bitcask - A Log-Structured Hash Table

Posted on May 4, 2023 • 12 minutes • 2487 words

Table of contents

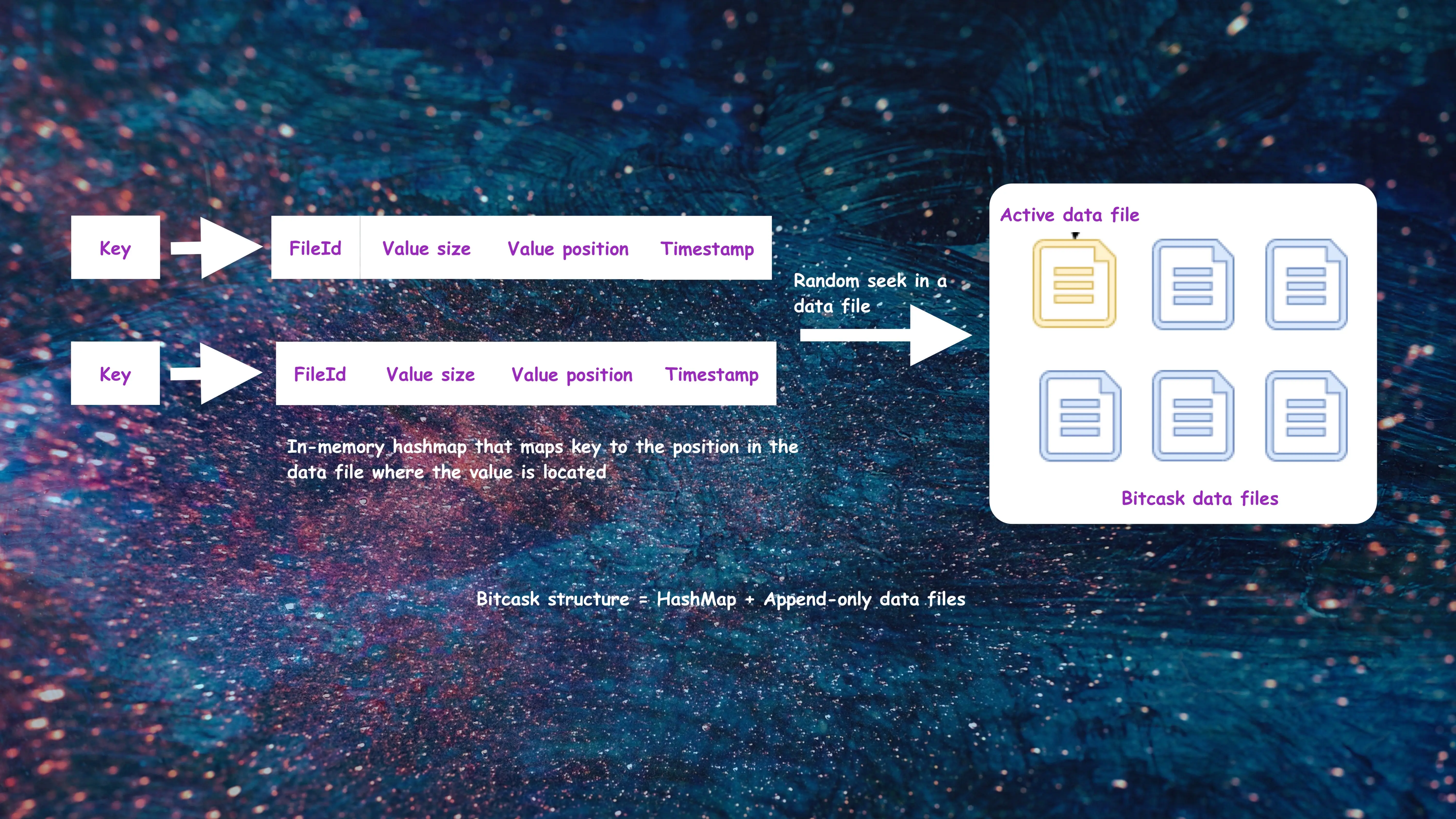

Bitcask is an embeddable key/value storage engine that is defined as a “Log-Structured Hash Table” in the paper that introduced it. Bitcask follows a simple model: all the key/value pairs are written to append-only files, and an in-memory data structure contains a mapping between each key and the position of the value in the data file.

Let’s understand the different components of Bitcask.

Bitcask components

Bitcask is a straightforward model to understand. It consists of two components:

- Append-only data files

- In-memory structure called

KeyDirthat maps each key to its value position in the data file

Let’s understand both these components.

Append-only data files

A bitcask instance consists of multiple data files on a disk. At any moment, only one file is active for writing. When that file meets a size threshold, it will be closed, and a new active file will be created. Once a file is closed, it is considered immutable and will never be opened for writing again.

The active file is written by appending, which means sequential writes are performed on disk. The format that is written for each key/value entry is simple:

┌─────┬───────────┬──────────┬────────────┐───────┐───────┐

│ CRC │ timestamp │ key_size │ value_size │ key │value │

└─────┴───────────┴──────────┴────────────┘───────┘───────┘

Every write involves appending a new entry to the active file. Even deletion is an append operation that involves writing a particular tombstone value. Thus, a Bitcask data file is a linear sequence of these entries.

KeyDir

KeyDir is simply a hash table that maps every key in Bitcask to a fixed-size structure giving the file, offset, and size of the most recently written entry for that key.

Let’s understand why Bitcask is both write and read-optimized.

Bitcask: Write-optimized storage engine

In Bitcask, each write results in a new entry being appended to a file. To do this, the underlying file is opened in the APPEND mode, and each entry is written to an increasing offset in the file. Thus, Bitcask performs sequential writes to the disk.

func NewStore(filePath string) (*Store, error) {

writer, err := os.OpenFile(filePath, os.O_WRONLY|os.O_APPEND, 0644)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return &Store{writer: writer}, nil

}

func (store *Store) append(bytes []byte) error {

bytesWritten, err := store.writer.Write(bytes)

if err != nil {

return err

}

if bytesWritten < len(bytes) {

return errors.New(fmt.Sprintf("Could not append %v bytes", len(bytes)))

}

return nil

}

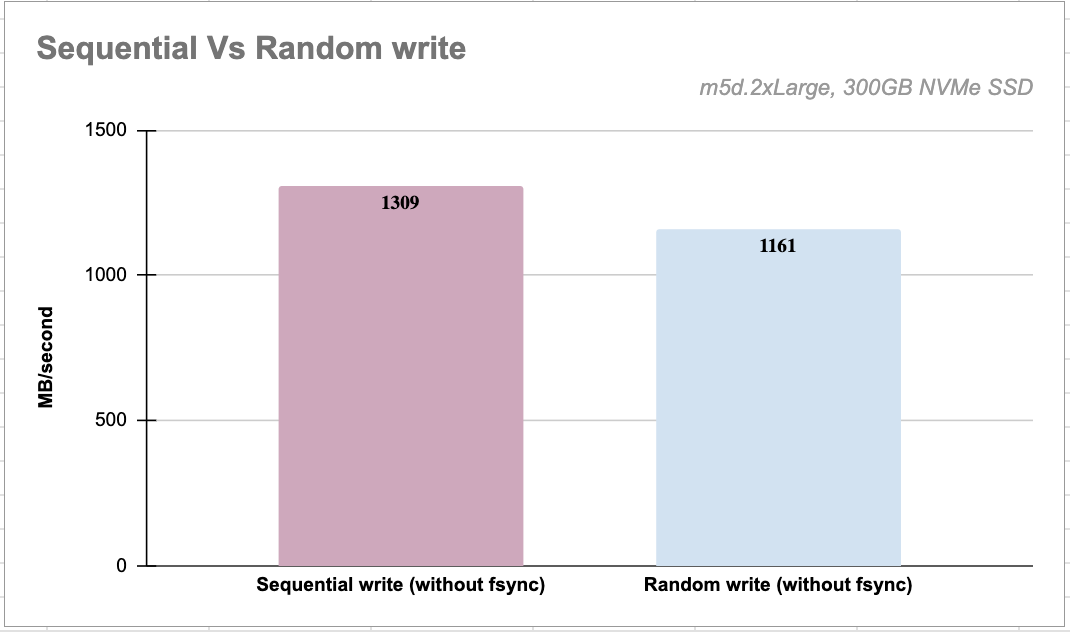

The image below highlights the throughput difference between sequential and random writes on an NVMe SSD; the difference would be much higher on an HDD.

Bitcask is write-optimized because it performs sequential writes to disk.

Bitcask: Read-optimized storage engine

Bitcask maintains all the keys in RAM in a data structure called KeyDir. A KeyDir is simply a hash table that maps every key in Bitcask to a fixed-size structure giving the file, offset, and size of the most recently written entry for that key.

One can imagine KeyDir to have the following structure:

type KeyDirectory[Key config.BitCaskKey] struct {

entryByKey map[Key]*Entry

}

type Entry struct {

FileId uint64

Offset int64

EntryLength uint32

Timestamp uint32

}

To read the value for a key a lookup operation is performed in the KeyDir to get the datafile and the value offset within it.

Once the Entry corresponding to the key is found in the KeyDir, a read operation is performed in the file identified by the Entry.FileId. This read operation involves performing a Seek to the offset defined by Entry.Offset in the file and then reading the entire byte slice ([]byte) identified by the Entry.EntryLength.

The correctness of the value retrieved is checked against the CRC stored and the value is then returned to the client.

This operation is fast as it involves performing a single disk seek. It can be made faster by using read-ahead system call.

The read operation can be represented with the following code:

func (kv *KVStore[Key]) Get(key Key) ([]byte, error) {

entry, ok := kv.keyDirectory.Get(key) (1)

if ok {

storedEntry, err := kv.segments.Read(entry.FileId, entry.Offset, entry.EntryLength) (2)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return storedEntry.Value, nil

}

return nil, errors.New(fmt.Sprintf("Key %v does not exist", key))

}

Step 1 performs a lookup in the KeyDir, and if an entry is present in the hash table, a disk read is performed in the file identified by the entry.FileId at an offset identified by entry.Offset.

Operations

Let’s understand various operations supported by Bitcask.

Put: put(key, value)

Every put operation appends the key/value pair to the active data file. Once the append operation to the data file is done, a new entry is created in the KeyDir

that maps the key to a fixed structure which contains the active fileId, value size, value position and timestamp.

The approach can be implemented as:

func (kv *KVStore[Key]) Put(key Key, value []byte) error {

appendEntryResponse, err := kv.segments.Append(key, value) (1)

if err != nil {

return err

}

kv.keyDirectory.Put(key, NewEntryFrom(appendEntryResponse)) (2)

return nil

}

kv.segments.Append(key, value)appends the key/value pair to the active segment(/data file)kv.keyDirectory.Put(key, NewEntryFrom(appendEntryResponse))creates a new entry in theKeyDirectory

My implementation uses the term Segment instead of Datafile and KeyDirectory instead of KeyDir.

Appending to the active segment

Let’s look at kv.segments.Append.

Before the key/value pair can be appended to the active segment file, the size of the active segment is checked against the maximum allowed size for a segment. If the active segment size has crossed the size threshold, it is rolled over (3). Rollover of the active segment involves creating a new active segment and adding the current active segment to the collection of inactive segments.

The key/value pair is then appended to the active segment. (4)

type Segments[Key config.BitCaskKey] struct {

activeSegment *Segment[Key]

inactiveSegments map[uint64]*Segment[Key]

maxSegmentSizeBytes uint64

}

type AppendEntryResponse struct {

FileId uint64

Offset int64

EntryLength uint32

}

func (segments *Segments[Key]) Append(key Key, value []byte) (*AppendEntryResponse, error) {

if err := segments.maybeRolloverActiveSegment(); err != nil { (3)

return nil, err

}

return segments.activeSegment.append(NewEntry[Key](key, value, segments.clock)) (4)

}

Encoding

The entry needs to be encoded to append it to the active segment.

Encoding is converting the key/value pair to a byte slice that can be written to the disk. The encoding scheme consists of the following structure:

┌───────────┬──────────┬────────────┬─────┬───────┐

│ timestamp │ key_size │ value_size │ key │ value │

└───────────┴──────────┴────────────┴─────┴───────┘

timestamp, key_size, value_size consist of 32 bits each. The value ([]byte) consists of the value provided by the user and a byte for tombstone, that

is used to signify if the key/value pair is deleted.

My implementation does not store CRC.

The encoding operation can be represented as:

type Entry[Key config.Serializable] struct {

key Key

value valueReference

timestamp uint32

clock clock.Clock

}

type valueReference struct {

value []byte

tombstone byte

}

func (entry *Entry[Key]) encode() []byte {

serializedKey := entry.key.Serialize()

keySize, valueSize := uint32(len(serializedKey)), uint32(len(entry.value.value))+tombstoneMarkerSize

encoded := make([]byte, reservedTimestampSize+reservedKeySize+reservedValueSize+keySize+valueSize)

var offset uint32 = 0

littleEndian.PutUint32(encoded, uint32(int(entry.clock.Now())))

offset = offset + reservedTimestampSize

littleEndian.PutUint32(encoded[offset:], keySize)

offset = offset + reservedKeySize

littleEndian.PutUint32(encoded[offset:], valueSize)

offset = offset + reservedValueSize

copy(encoded[offset:], serializedKey)

offset = offset + keySize

copy(encoded[offset:], append(entry.value.value, entry.value.tombstone))

return encoded

}

The little-endian system stores the least-significant byte at the smallest address.

Putting in the KeyDirectory

Let’s look at the last step of put operation, kv.keyDirectory.Put.

After the append operation is done, a new entry is created and inserted into the hashmap.

type KeyDirectory[Key config.BitCaskKey] struct {

entryByKey map[Key]*Entry

}

func (keyDirectory *KeyDirectory[Key]) Put(key Key, value *Entry) {

keyDirectory.entryByKey[key] = value

}

Update: update(key, value)

The update operation is similar to the put operation. It appends the key/value pair to the active segment file and updates the existing entry in the KeyDirectory

with the new position and possibly with the new fileId.

All the key/value storage engines that rely on append-only log files can have the same key with different values across different data files. To remove old entries, merge and compaction process has to be introduced to merge data files and produce a set of data files containing only the latest versions of each present key.

Delete: delete(key)

Delete operation appends a new entry to the active segment with a tombstone marker to signify deletion. Once the entry is appended to the active segment, an in-place delete is performed in the KeyDirectory to remove the key.

The approach can be represented with the following code:

func (kv *KVStore[Key]) Delete(key Key) error {

if _, err := kv.segments.AppendDeleted(key); err != nil { (1)

return err

}

kv.keyDirectory.Delete(key) (4)

return nil

}

func (segments *Segments[Key]) AppendDeleted(key Key) (*AppendEntryResponse, error) {

if err := segments.maybeRolloverActiveSegment(); err != nil { (2)

return nil, err

}

return segments.activeSegment.append(NewDeletedEntry[Key](key, segments.clock)) (3)

}

func NewDeletedEntry[Key config.Serializable](key Key, clock clock.Clock) *Entry[Key] {

return &Entry[Key]{

key: key,

value: valueReference{value: []byte{}, tombstone: 1},

timestamp: 0,

clock: clock,

}

}

The above code can be summarized as:

- The

Deletemethod of KVStore calls theAppendDeletedofSegments - The

AppendDeletedmethod rolls over the active segment if the size of the active segment has crossed the segment size threshold - The

AppendDeletedmethod creates anEntrywith thetombstonebyte set to 1 to indicate the deletion - After the entry is appended to the active segment, the key is deleted from the

KeyDirectory

Because the delete operation is append-only, the merge and compaction process removes the deleted entries from the segment files and retains only the non-deleted keys.

My implementation of delete maintains a separate tombstone byte to indicate the deletion. However, Bitcask paper mentions appending a particular tombstone value.

Get: get(key)

To read the value for a key, a lookup operation is performed in the KeyDir to get the datafile and the value offset within it.

Once the Entry corresponding to the key is found in the KeyDir, a read operation is performed in the file identified by the Entry.FileId. This read operation involves performing a Seek to the offset defined by Entry.Offset in the file and then reading the entire byte slice ([]byte) identified by the Entry.EntryLength.

The read operation can be represented with the following code:

func (kv *KVStore[Key]) Get(key Key) ([]byte, error) {

entry, ok := kv.keyDirectory.Get(key) (1)

if ok {

storedEntry, err := kv.segments.Read(entry.FileId, entry.Offset, entry.EntryLength)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

return storedEntry.Value, nil

}

return nil, errors.New(fmt.Sprintf("Key %v does not exist", key))

}

func (segments *Segments[Key]) Read(fileId uint64, offset int64, size uint32) (*StoredEntry, error) {

if fileId == segments.activeSegment.fileId { (2)

return segments.activeSegment.read(offset, size)

}

segment, ok := segments.inactiveSegments[fileId] (3)

if ok {

return segment.read(offset, size)

}

return nil, errors.New(fmt.Sprintf("Invalid file id %v", fileId))

}

func (segment *Segment[Key]) read(offset int64, size uint32) (*StoredEntry, error) {

bytes, err := segment.store.read(offset, size) (4)

if err != nil {

return nil, err

}

storedEntry := decode(bytes) (5)

return storedEntry, nil

}

The above code can be summarized as:

- Perform a lookup in the

KeyDirectoryand get an entry containing thefileId,entry positionandentry size - Read from the active segment if the

fileIdmatches the active segment’sfileId - Read from the inactive segment if the

fileIdmatches one of the inactive segment’sfileId - Perform a

File.Read()and get a byte slice decodethe read bytes to get the actual entry

Merge and compaction

Any storage engine model built on top of append-only data files like LSM or bitcask may use up much disk space over time, since new values are appended to the files without touching the old ones. Therefore, a process for compaction that is referred to as “merging” is required. The merge process iterates over all non-active (i.e. immutable) files in a Bitcask instance and produces a set of data files containing only the “live” or the latest versions of each present key.

Merge process needs to read all the immutable data files in memory, keep the live and the latest version of each key, and write the merged state back to disk in form of new immutable data files.

After the merged state is written back to the disk, the in-memory state of the keys need an update because the keys now exist in a different data file.

func (worker *Worker[Key]) beginMerge() {

var fileIds []uint64

var segments [][]*log.MappedStoredEntry[Key]

fileIds, segments, err

:= worker.kvStore.ReadAllInactiveSegments(worker.config.KeyMapper()) (1)

if err == nil && len(segments) >= 2 {

mergedState := NewMergedState[Key]()

mergedState.takeAll(segments[0])

for index := 1; index < len(segments); index++ {

mergedState.mergeWith(segments[index]) (2)

}

_ = worker.kvStore.WriteBack(fileIds, mergedState.valueByKey)

}

}

func (kv *KVStore[Key]) WriteBack(fileIds []uint64, changes map[Key]*appendOnlyLog.MappedStoredEntry[Key]) error {

writeBackResponses, err := kv.segments.WriteBack(changes) (3)

if err != nil {

return err

}

kv.keyDirectory.BulkUpdate(writeBackResponses) (4)

kv.segments.Remove(fileIds) (5)

return nil

}

The above code can be summarized as:

- Read all the inactive segments in the RAM

- Perform the merge operation.

MergeStatemaintains a hashmap to keep only one version of each key. The timestamp is used to decide the latest version of a key - Write back the merged state to new immutable data files on the disk

- Update the

KeyDirectoryto ensure that the keys point to the updated data file - Remove old data files from the disk

Hint file

The crash recovery for a Bitcask instance will require reading all the data files and reloading the state of KeyDir. This process is expensive because it needs to read large data files. Bitcask proposes hint files

to speed up the recovery process (or the boot process).

When the merge begins, it creates a hint file next to each data file. Hint files are like the data files but instead of the values, they contain keys and the position and size of the values within the corresponding data file. Hint files are smaller than data files because they don’t contain values. Hence, recovery is done from hint files instead of data files.

Conclusion

Bitcask has a relatively simple data structure compared to LSM , and it offers some great positives:

- High write throughput: it performs sequential disk writes, offering high write throughput.

- Low latency per item read or written: all the operations require a single disk seek.

- Ease of backup and restore: since the data files are immutable, backup can be taken by copying the directory. Restoration requires nothing more than placing the data files in the desired directory.

- Crash friendliness: As the data files and the commit log are the same things in Bitcask, recovery is trivial.

- A relatively simple model to understand.

Bitcask model has a set of challenges:

- High memory usage: Bitcask stores all the keys in RAM. Thereby the memory usage is high. However, if the keys can be partitioned the problem can be reduced to some extent.

- Huge number of open OS file handles: Get operation in Bitcask can happen from both the active and inactive segment files, and there could be large number of inactive segment files in a single Bitcask instance. To perform a read from an inactive segment, we might want to keep the file pointer of the inactive segment file open. This can result in too many open OS file handles.

Code

The code for this article is available here .