Bloom filter

Background by Paola Galimberti on Unsplash

Table of contents

A Bloom filter is a probabilistic data structure1 used to test whether an element is a set member. A bloom filter can query against large amounts of data and return either “possibly in the set” or “definitely not in the set”.

A bloom filter can have false positives, but false negatives are impossible.

Elements can only be added to the set, but not removed (though this can be addressed with the counting bloom filter variant).

Burton Howard Bloom conceived the Bloom filter in 1970.

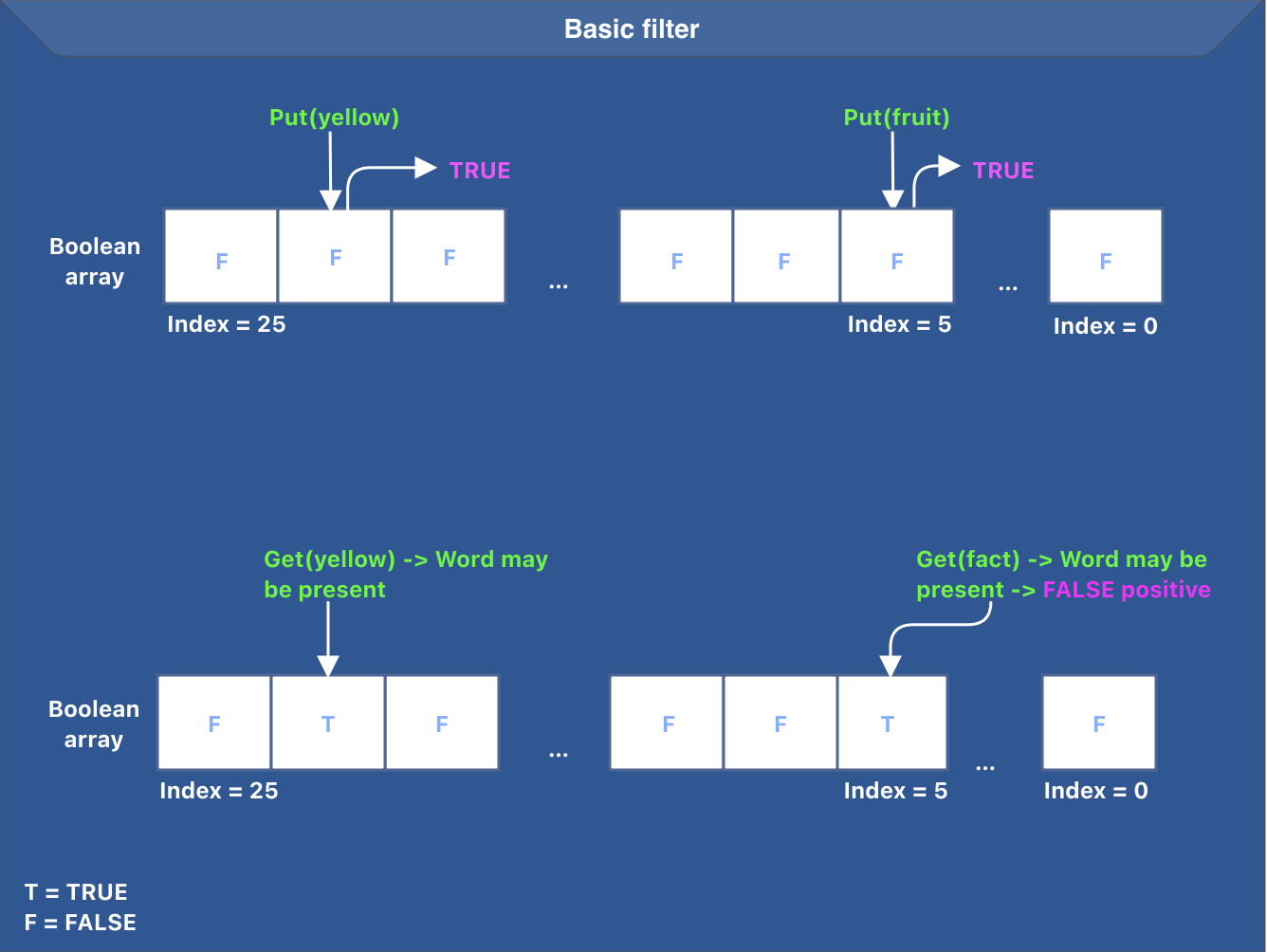

A basic filter

Let’s build a basic filter for a giant persistent dictionary of lowercase English words. Here are some requirements for this filter:

- It should not take more than 26 bytes of memory

- It should return either possibly in the set or definitely not in the set

- Our application will query the filter first, and only if the filter returns “possibly in the set” will the application query the persistent dictionary

One idea to design such a filter would be to maintain a boolean array of size 26 (26 lowercase English letters) to indicate the presence of a word beginning with a character.

The filter does not store the actual word; it only indicates the presence of a word. The word gets added to the persistent dictionary after adding it to the basic filter. To do that, we set the value at the array index corresponding to the first letter to true.

To check if the dictionary contains a word, the application queries the filter first. The filter checks the value at the index corresponding to the first letter [firstLetterOfTheWord-asciiCodeOf('a')] and returns true if the value at the index is set, false otherwise.

Let’s understand the returned values from the filter:

- If the returned value is

false, we can conclude that the word is not present in the persistent dictionary - If the returned value is

true, we can not be sure if the word is present because there may be multiple words starting with the same letter

The idea behind the basic filter is presented in the image below.

The image above also highlights a false positive case for the word “fact”.

Understanding bloom filter

We should extend the idea of the basic filter to build a bloom filter. There are two main issues with our basic filter:

- The

booleanarray of size 26 is too small. There are billions of words in English, and an array of size 26 will cause too many false positives - We use a single hash function to determine the array position to set or read. This hash function is

firstLetterOfTheWord-asciiCodeOf('a')

The solution to both these problems takes us closer to the bloom filter. The bloom filter uses two main concepts:

- M-sized bit vector

- K hash functions

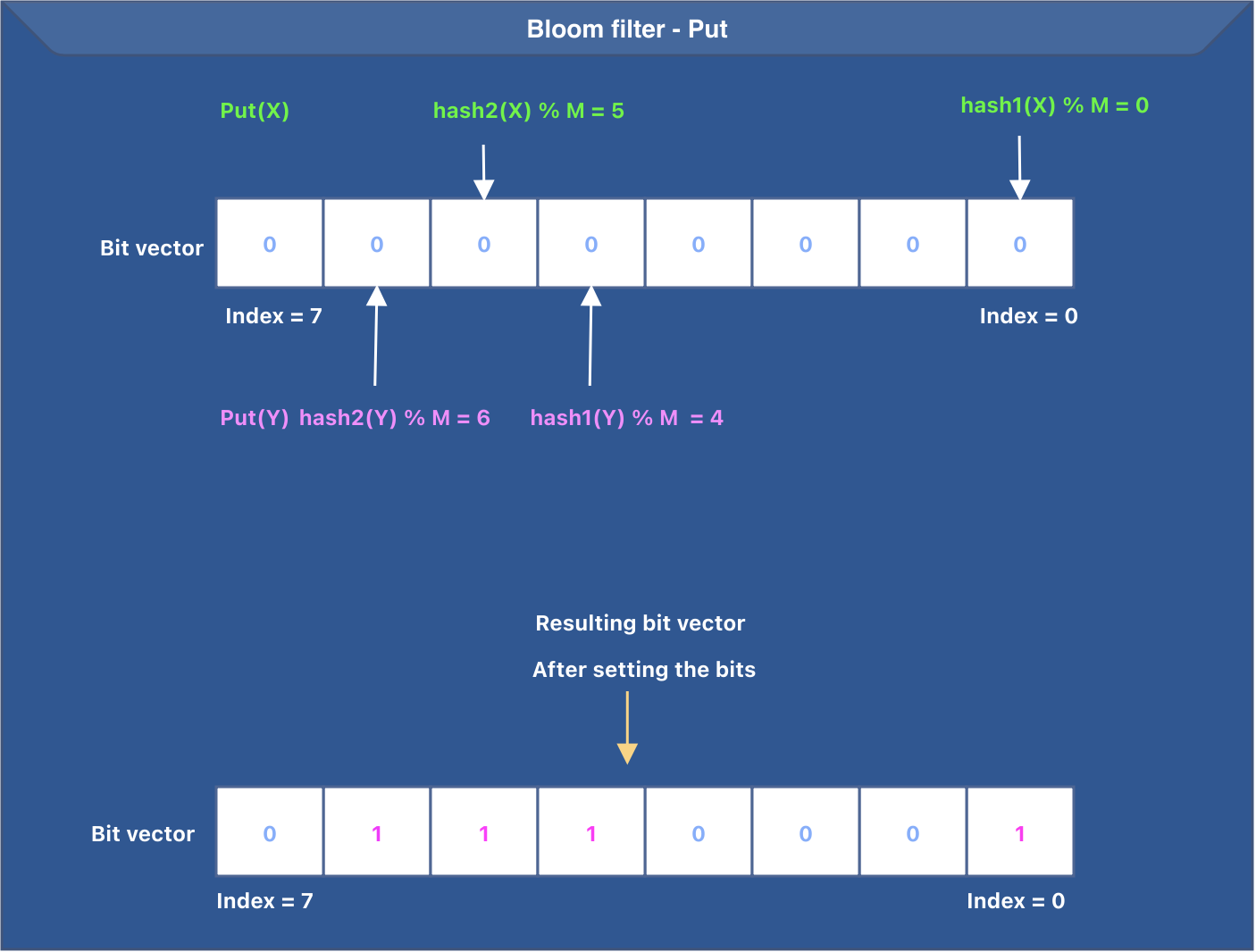

The bloom filter maintains a bit array of size M; every key goes through K hash functions to determine the bit position to set.

MandKneed to be computed.

Bloom filter supports two operations:

putthat puts a key in the bloom filterhasthat returns either possibly in the bloom filter or definitely not in the bloom filter

Let’s summarize the working of the put operation. To put a key in the bloom filter, the following steps are performed:

- The input key goes through K hash functions.

- The output of every hash function is reduced to a value between

0 and M-1to set the appropriate bit in the bit vector. - The corresponding bit is set in the bit vector.

Every input goes through K hash functions, setting at most K bits in the bit vector.

The idea behind the put operation is presented in the image below. In the below image, we have K=2 (total hash functions) and M=8 (bit vector size).

Remember, a bloom filter does not store the actual key; it only indicates the presence of a key by using at most K bits in an M-sized bit vector.

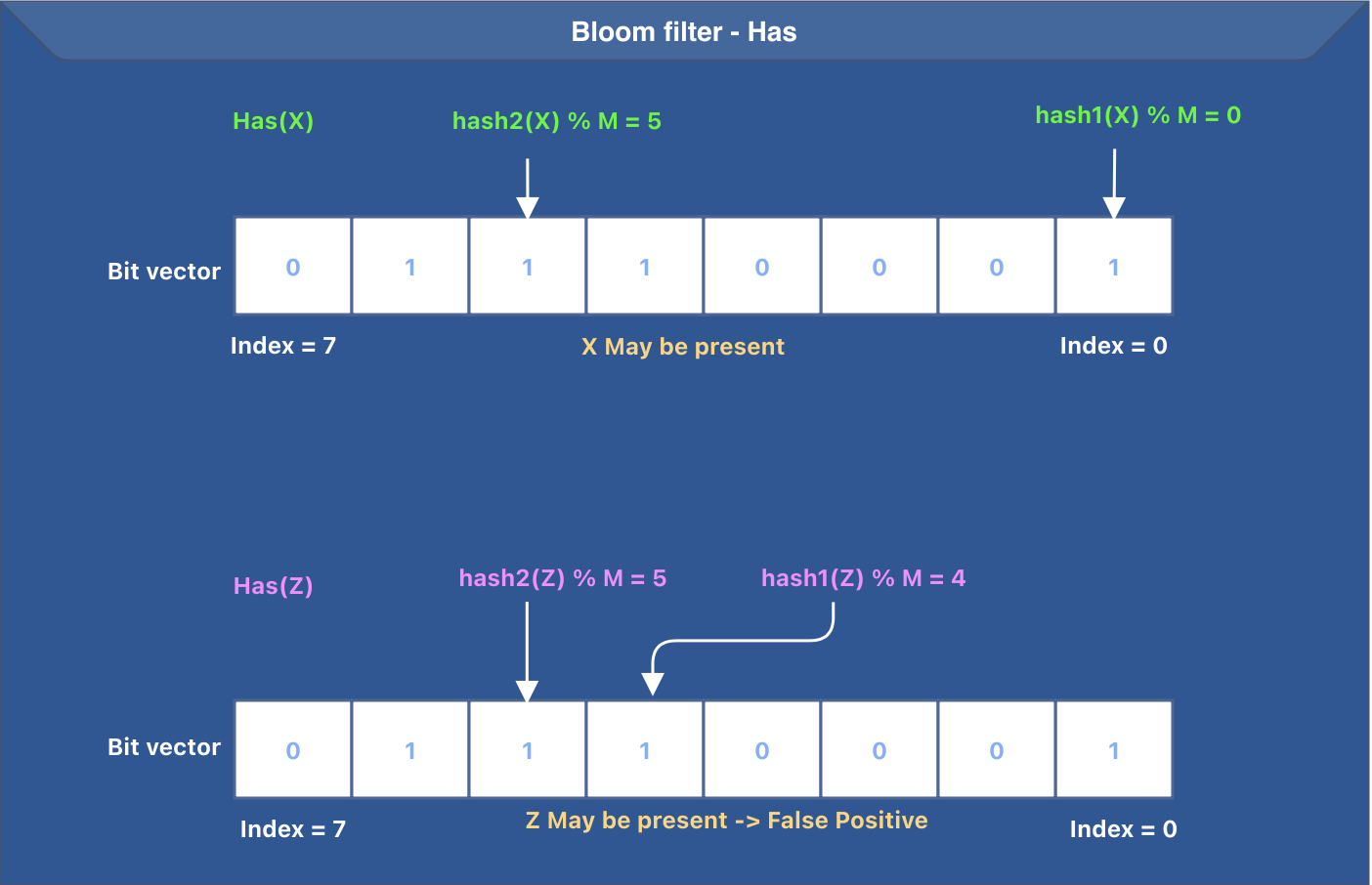

Let’s summarize the working of the has operation. To determine if a key maybe present in the bloom filter, the following steps need to be performed:

- The input key goes through K hash functions.

- The output of every hash function is reduced to a value between

0 and M-1to get the appropriate bit in the bit vector. - The corresponding bit is checked to see if it is set. If the bit is not set, we return

false. - We return

trueif all the bits determined from steps 1 and 2 are set.

The idea behind the has operation is presented in the image below. We are using the same bit vector that was generated after the put operations were done. In the below image, we have K=2 (total hash functions) and M=8 (bit vector size).

Bloom filters can have false positives. The image above represents a false positive for the input Z.

Adding tests for put and has

Let’s add a couple of tests for put and has and understand them.

func TestAddsAKeyAndChecksForItsPositiveExistence(t *testing.T) {

bloomFilter := newBloomFilter(20, 0.001) //takes capacity and false positive rate

key := model.NewSlice([]byte("Company"))

bloomFilter.Put(key)

if bloomFilter.Has(key) == false {

t.Fatalf("Expected %v key to be present but was not", key.AsString())

}

}As a part of this test, we do the following:

- Create a new bloom filter with

capacity=20andfalsePositiveRate=0.001 - Create a new key of type

model.Slice. Keys are represented bySliceabstraction, which is a wrapper over a byte slice. - Put the key in.

- Assert that the key is present in the bloom filter

A bloom filter can never have false negatives. So, we can be sure that the above assertion will always succeed.

func TestAddsAKeyAndChecksForTheExistenceOfANonExistingKey(t *testing.T) {

bloomFilter := newBloomFilter(20, 0.001) //takes capacity and false positive rate

key := model.NewSlice([]byte("Company"))

bloomFilter.Put(key)

if bloomFilter.Has(model.NewSlice([]byte("Missing"))) == true {

t.Fatalf("Expected %v key to be missing but was present", model.NewSlice([]byte("Missing")).AsString())

}

}This test is very much similar to the previous one. As a part of this test, we want to assert that the given key should not be present in the bloom filter.

A test of this nature can fail in the case of a false positive.

Now is the right time to build a bloom filter.

Building bloom filter

Let’s understand the structure of BloomFilter before we get into the functions.

type BloomFilter struct {

capacity int

numberOfHashFunctions int

falsePositiveRate float64

bitVector *bitset.BitSet

bitVectorSize uint

}

func newBloomFilter(capacity int, falsePositiveRate float64) *BloomFilter {

//determine the number of hash functions

numberOfHashFunctions := numberOfHashFunctions(falsePositiveRate)

//determine the bit vector size

bitVectorSize := bitVectorSize(capacity, falsePositiveRate)

//create a new instance of BloomFilter with a bit vector of determined size

return &BloomFilter{

capacity: capacity,

numberOfHashFunctions: numberOfHashFunctions,

falsePositiveRate: falsePositiveRate,

bitVector: bitset.New(uint(bitVectorSize)),

bitVectorSize: uint(bitVectorSize),

}

}The idea behind newBloomFilter function can be summarized as:

- Determine the number of hash functions (K)

- Determine the bit vector size (M)

- Create a new instance of

BitSetusingbitset.New(...). - Return a new instance of

BloomFilter

The field

bitVectorinside theBloomFilterstruct is a pointer tobitset.BitSet. We use the bitset package offered by the library bits-and-blooms.

The values of K and M are calculated using the below functions.

//calculate numberOfHashFunctions(K)

func numberOfHashFunctions(falsePositiveRate float64) int {

return int(math.Ceil(math.Log2(1.0 / falsePositiveRate)))

}

//calculate bitVectorSize(M)

func bitVectorSize(capacity int, falsePositiveRate float64) int {

//ln22 = ln2^2

ln22 := math.Pow(math.Ln2, 2)

return int(float64(capacity) * math.Abs(math.Log(falsePositiveRate)) / ln22)

}Now that we have determined the K and M values let’s implement Put. The idea can be summarized as follows:

- Run

Khash functions or a single hash function with different seed values,Ktimes over an input. - Reduce the hashed value between

0 and M-1to set the appropriate bit in the bit vector. - Set the bit in the bit vector at the identified position.

This is how the above approach can be implemented:

func (bloomFilter *BloomFilter) Put(key model.Slice) {

//get the bit vector indices to set

indices := bloomFilter.keyIndices(key)

for index := 0; index < len(indices); index++ {

position := indices[index]

//set the bit at the identified position

bloomFilter.bitVector.Set(uint(position))

}

}

// Use the hash function to get all keyIndices of the given key

func (bloomFilter *BloomFilter) keyIndices(key model.Slice) []uint64 {

indices := make([]uint64, 0, bloomFilter.numberOfHashFunctions)

runHash := func(key []byte, seed uint32) uint64 {

hash, _ := murmur3.Sum128WithSeed(key, seed)

return hash

}

indexForHash := func(hash uint64) uint64 {

//index = hash % M

return hash % uint64(bloomFilter.bitVectorSize)

}

for index := 0; index < bloomFilter.numberOfHashFunctions; index++ {

//run murmur3 hash for the given key with index as the seed

hash := runHash(key.GetRawContent(), uint32(index))

//identify the index between 0 and M-1 and return the indices

indices = append(indices, indexForHash(hash))

}

return indices

}Let’s implement Has. The idea can be summarized as follows:

- Run

Khash functions or a single hash function with different seed values,Ktimes over an input. - Reduce the hashed value between

0 and M-1to get the appropriate bit in the bit vector. - Check the bit in the bit vector at the identified position. If the bit is not set, return

falseto indicate that the input is absent. - If the bits at all the identified positions are set, return

trueto indicate that the input may be present.

This is how the above approach can be implemented:

func (bloomFilter *BloomFilter) Has(key model.Slice) bool {

//get the bit vector indices

indices := bloomFilter.keyIndices(key)

for index := 0; index < len(indices); index++ {

position := indices[index]

//test the bit at the identified position, return false if the bit is not set

if !bloomFilter.bitVector.Test(uint(position)) {

return false

}

}

return true

}Space-optimized data structure

Bloom filter is a space-optimized data structure that does not store the keys. Let’s see the total space we need to hold half a million keys in the bloom filter.

The values of K and M were calculated using the following functions.

//calculate numberOfHashFunctions(K)

func numberOfHashFunctions(falsePositiveRate float64) int {

return int(math.Ceil(math.Log2(1.0 / falsePositiveRate)))

}

//calculate bitVectorSize(M)

func bitVectorSize(capacity int, falsePositiveRate float64) int {

//ln22 = ln2^2

ln22 := math.Pow(math.Ln2, 2)

return int(float64(capacity) * math.Abs(math.Log(falsePositiveRate)) / ln22)

}Let’s run these functions for the 500000 keys and 0.001 as the false positive rate.

func main() {

numberOfHashFunctions := numberOfHashFunctions(0.001)

bitVectorSize := bitVectorSize(500000, 0.001)

println("numberOfHashFunctions::", numberOfHashFunctions)

println("bitVectorSize::", bitVectorSize)

}The above code prints numberOfHashFunctions:: 10 bitVectorSize:: 7188793. This means a total space of 878KB ((7188793/8)/1024) for storing 500000 keys.

Now is the right time to understand how BadgerDB uses bloom filters.

BadgerDB

Bloom filter is used in a lot of projects, including BadgerDB and Apache Spark. This article explains the way the bloom filter is used in BadgerDB.

BadgerDB is an embeddable, persistent, fast key-value (KV) database written in pure Go. Badger’s design is a combination of an LSM tree2 with a value log and is based on a paper titled WiscKey: Separating Keys from Values in SSD-conscious Storage

A log-structured merge tree (LSM tree) is a storage engine data structure typically used when dealing with write-heavy workloads. The write path is optimized by performing sequential writes on the disk. To perform sequential writes on disk, the LSM tree buffers the data in memory and then flushes to disk once the in-memory buffer is full. To ensure the durability of the data, every write is first added to a WAL (write-ahead log) file before updating the in-memory buffer. The in-memory buffer is called the memtable. After the memtable is full, it is converted to SSTable (sorted string table) and flushed to disk.

Every get(key) operation first queries the in-memory memtable(s) to see if the value for the given key exists in memory. If not, the get(key) operation retrieves the value from SSTables (disk-based structures).

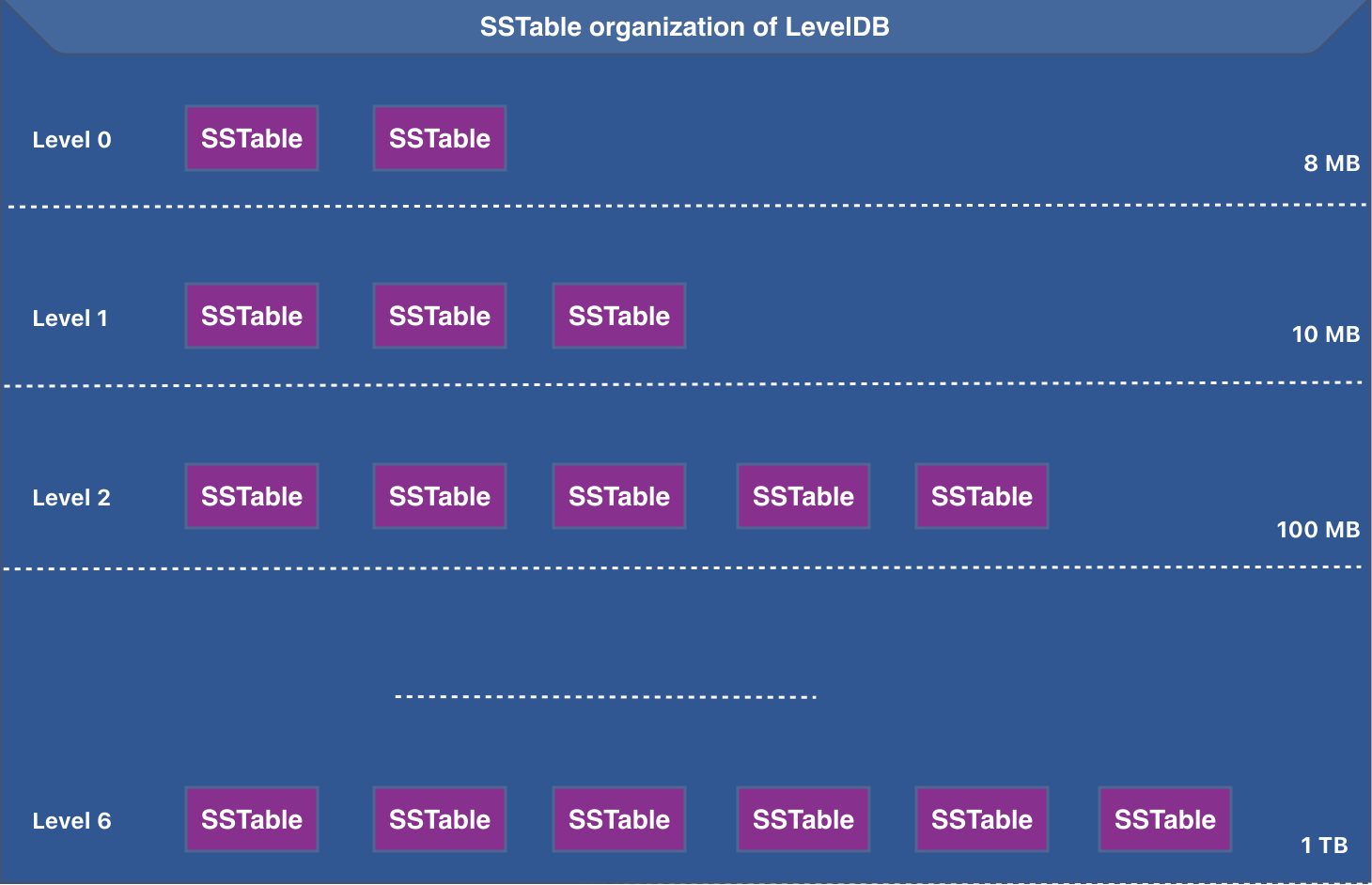

SSTables are organized into levels. Below is the organization of SSTables in LevelDB

The size of the SSTables (or the files) increases as we go down the levels.

One way to perform a get(key) operation on SSTables is to scan all the SSTables starting from level=0 to level=N and return the value as soon as it is found. This approach is brute-force, and it means a lot of IO costs.

This approach can be optimized by using a bloom filter. Let’s see how:

- Every SSTable can be associated with its filter.

- All the keys of an SSTable will be added to its bloom filter.

SSTable (sorted string table) contains all the key-value pairs sorted by key. SSTable file is organized into multiple sections (or blocks), including index block, bloom filter block, data block and footer block etc. BadgerDB puts the bloom filter (the byte array of the bloom filter) inside the SSTable.

To perform a get(key) operation on an SSTable, the application will query the bloom filter associated with it.

To query the bloom filter associated with an SSTable, the bloom filter block (byte array) needs to be read in memory. The information about the begin and the end offsets of the bloom filter is encoded in the footer block of the SSTable.

If the bloom filter returns true, the application will scan the data block of the SSTable to get the value of the given key. This also means that the bloom filter will check an SSTable even in the case of false positives.

Let’s now look at BadgerDB’s code to understand the use of the bloom filter.

//some fields omitted

type levelsController struct {

levels []*levelHandler

}

//get searches for a given key in all the levels of the LSM tree starting with startLevel

//code omitted

func (s *levelsController) get(key []byte, maxVs y.ValueStruct, startLevel int) (y.ValueStruct, error) {

version := y.ParseTs(key)

for _, level := range s.levels {

// Ignore all levels below startLevel. This is useful for GC when L0 is kept in memory.

if level.level < startLevel {

continue

}

//invoke levelHandler to get the value for the given key

valueStruct, err := level.get(key)

if valueStruct.Version == version {

return valueStruct, nil

}

}

return maxVs, nil

}SSTables are organized into multiple levels and levelsController is an abstraction to represent these levels. Each level is represented by another abstraction called levelHandler. levelsController maintains an array of levels or levelHandler. The get method does the following:

- Scan through all the levels greater than or equal to the

startLevel. - For each level, ask the

levelHandlerto get the value for the key by invokinglevel.get(key). - Match the key version and return the received value if it matches.

levelHandler represents a level and maintains an array of all the SSTables for that level. get method attempts to return the value with the latest version:

//some fields omitted

type levelHandler struct {

tables []*table.Table

level int

}

// get returns value for a given key or the key after that. If not found, return nil.

func (lHandler *levelHandler) get(key []byte) (y.ValueStruct, error) {

tables, decr := lHandler.getTableForKey(key)

//get the key without a timestamp

keyNoTs := y.ParseKey(key)

//get the hash of the key

hash := y.Hash(keyNoTs)

var maxVs y.ValueStruct

for _, table := range tables {

//if the table does not have the hash of the key, there is no point in scanning the table

//(*) bloom filter lookup

if table.DoesNotHave(hash) {

continue

}

//create an iterator over the table

iterator := table.NewIterator(0)

defer iterator.Close()

//seek to the key in SSTable

iterator.Seek(key)

if !iterator.Valid() {

continue

}

//store the value with the maximum version

if y.SameKey(key, iterator.Key()) {

if version := y.ParseTs(iterator.Key()); maxVs.Version < version {

maxVs = iterator.ValueCopy()

maxVs.Version = version

}

}

}

return maxVs, decr()

}The working of the get method of levelHandler can be summarized as:

- Get the hash of the key without a timestamp.

- Iterate through the tables (SSTables) and if the current table does not contain the given key, skip it and move to the following table.

- If the table can contain the given key, create an iterator over the table.

- Use

iterator.Seekto seek to the given key. - Store the value of the matching key only if its version is greater than the existing version.

- Return the value (value is represented by

ValueStruct).

table.DoesNotHave(hash) does a bloom filter lookup. DoesNotHave returns true if the table does not have the key.

Code

The code for this article is available here.

Mention

Thank you, Debasish Ghosh for reviewing the article and providing feedback.

References

Footnotes

-

Probabilistic data structures provide approximate answers to queries about a large dataset rather than exact answers. These data structures are designed to handle large amounts of data in real-time by making trade-offs between accuracy and time and space efficiency. ↩

-

LSM Tree A log-structured merge tree (LSM tree) is a data structure typically used when dealing with write-heavy workloads. The write path is optimized by performing sequential writes. ↩